A recurring theme in software development is how to grow systems over time whilst keeping control of complexity. The industry is constantly awash with ideas on how to achieve this, from Hexagonal Architecture to Microservices and CQRS, making the decision of which path to follow increasingly tough.

At Black Pepper we like to trial new approaches to best understand how they can benefit our development teams and ultimately our customers. We recently adopted the Hexagonal Architecture pattern (also known as Ports & Adapters) on one of our projects and were pleased with the outcome.

Hexagonal Architecture

As enticing as the name sounds, the ideas behind Hexagonal Architectures aren’t particularly new; in fact, one may argue that it is essentially about programming to interfaces, rather than concrete implementations, which has been the bedrock of object orientated programming for decades. The difference really lies in how much further this approach takes the idea.

The aim of the Hexagonal Architecture is to distil the crux of an application into a discrete standalone module. Any dependencies on external services are factored out to a ‘port’ that the application communicates over (an API) and an ‘adapter’ that provides the service (the API implementation). This approach is taken not just for the obvious services, such as sending emails, reading a data feed or accessing a database (‘secondary ports’), but also for subservient services such as the user interface (‘primary ports’).

The motivation behind such extreme abstraction is to allow as much of the application to be tested in isolation as possible. For example, an automated test adapter could be plugged into the user interface port to enable programmatic use of the application. A fake database adapter could also be plugged into the data access port to spare the tests from firing up a real database. Having strong barriers in place for an application’s boundaries removes the temptation to put smarts into adapters, such as business logic in the user interface or the database, making the application easier and faster to test.

Don’t be mislead into thinking that the name ‘hexagonal architecture’ places any significance on the number six; it is simply named so to provide space for up to six potential ports when drawing architectural diagrams.

What does this look like?

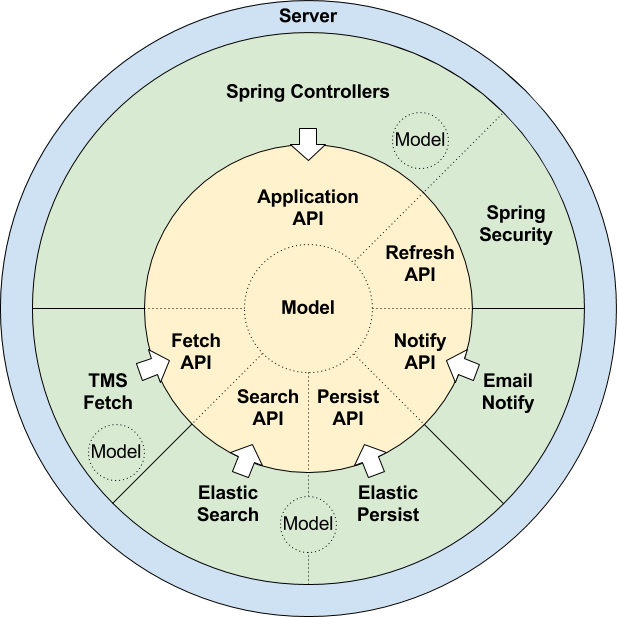

This all sounds great, but what does a real life hexagonal architecture look like? Below is an architectural diagram of the server component from one of our projects (I used concentric circles instead of hexagons for ease of drawing):

In this diagram the yellow inner circle depicts the essence of the application; the ‘hexagon’ itself. This contains the various APIs together with the white arrows that denote the ports. Plugging into these ports are the adapters that are represented by the green segments. The outer blue ring is the server that assembles and configures the various components to produce the runtime binary. Finally, the solid black lines show module boundaries which are distinct compilation units, whereas the dashed black lines demonstrate logical partitions within a module that could be broken apart if desired.

Each adapter isolates its own dependencies to keep the API implementation-agnostic. In this application, Spring Boot is constrained to the UI adapter rather than being integral to the system. Similarly, the persistence adapter is the only module aware of Elasticsearch. Maintaining this strong separation does require some discipline as many frameworks make it all too easy to tightly couple these aspects together.

You’ll notice a number of models in this diagram: a central domain model shared by all the APIs; and further implementation specific models in some of the adapters. This separation allows adapters to coerce the API model into a shape suitable for the underlying implementation. For example, the Elasticsearch persistence module converts the API model into a JSON object suitable for serialisation. Conversion between models takes place at the port boundary by the adapter to prevent implementation details from leaking into the API.

On reflection

Starting a greenfield project with this architecture can initially feel like over engineering, as each sliver of functionality introduces further APIs, more modules, and their respective models and converters. Nevertheless, at a certain application size, which I surmise would be encountered within a few months of development, the architectural discipline starts to pay off. The isolated and focused nature of individual modules helps manage complexity to produce software that fits in developers’ heads, much as I imagine microservices would continue this trend as the hexagon grows.

Since defining ports has such a profound effect on the software design, I would certainly encourage those interested to adopt this architecture earlier rather than later. Much like writing tests, it becomes increasingly more expensive to retrofit. Decoupling adapters from the application also provides much greater freedom to switch implementation technologies at a later date; no longer does a framework have to permeate the entire application. One challenge that does arise is managing the many models that emerge under this approach if written manually, so consider minimising the boilerplate required by using tools such as Immutables.

Overall the experience has been a positive one and is something I would recommend for any non-trivial project.