Last year I wrote about my quest to understand the artificial intelligence technique of neuroevolution. This form of AI builds upon classic neural networks by removing the need for supervised learning. Instead, genetic algorithms are used to evolve the structure of the network without human intervention.

My plan was to use neuroevolution to learn how to play a simple video game, but sadly I ran out of time. Fast forward to the end of the year and we had the opportunity to run a week-long experiment of innovation at Black Pepper. Four of us decided to try mob programming, and continuing where I left off, see if we could evolve a video games master.

Let the games begin

We first needed to decide on a game for our bot to play. The choice depended on whether to use an emulator to play a real game, or whether to write a simple game from scratch. We settled on the latter for two reasons: it would allow us to modify the game dynamics and observe how it affected the AI; and we wouldn’t have to learn how to programmatically control an emulator and obtain game state for our bot to base decisions upon.

With this in mind we opted for the video game classic Pong. My original neuroevolution code was in Java so we wrote a simple Pong clone in Swing, keeping the game graphics lo-res and omitting match score for simplicity. At this point both players had manual controls so we could enjoy play testing the game.

Humans playing Pong

Humans playing Pong

Ready player one

Now that we had the basic infrastructure in place the next step was to start wiring up the neuroevolution library to the game. If this blog post were a film then this part would be the montage. Alas, we were deprived of such luxury and duly proceeded to break this nebulous task into manageable chunks.

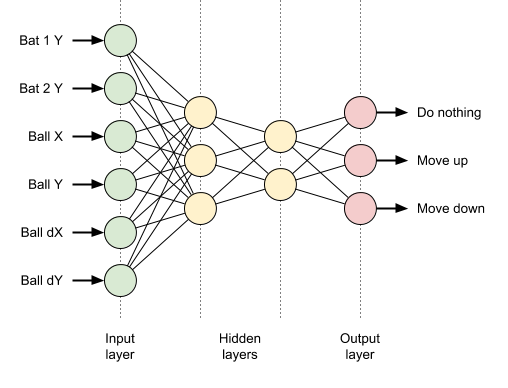

We decided that the simplest form of integration would be to take a genome, which in neuroevolution is a neural network, feed it the game state, and then use the output to move the player. This required us to tie down exactly what the inputs and outputs of the network would be.

If we were playing a more complicated game than Pong then a reasonable approach for the inputs would be to map each node to a lo-res pixel. This felt like an overkill for Pong though, so we settled on six input nodes mapped to the following game state: the bats’ positions, the ball’s coordinates, and the ball’s velocities.

The outputs seemed more obvious. In Pong the player can either move the bat up or down. Less apparent is that they can also elect to do nothing, which we included as an option to encourage the bot to be less hyperactive. Thus we modelled the outputs with three nodes, one for each option, where the strongest signal wins.

Now that we could supply the inputs and act upon the outputs, the remaining task was to feed the data through the network to connect them up. Intuitively one envisages the data propagating forward through the network, indeed this is how classic matrix-based forward propagation is implemented, but with an irregular shaped network it was actually simpler to pull data from the output nodes. This was predominantly due to recursion providing a more concise solution to evaluating a variable number of different sized hidden layers.

We now had enough pieces of the puzzle to assemble our first bot. To validate this we created a random neural network, and with a fortuitous strike of lightning, unleashed it onto a game of Pong and declared it’s alive!

A random genome twitching

A random genome twitching

Witness the fitness

One genome playing Pong was a good start, but to harness genetic algorithms we needed entire populations to play Pong. Alongside this we also required a method to identify strong contenders by assigning a fitness score to each one.

We expanded our single genome to an initial population of random genomes and played them out sequentially. To measure their success we simply counted the number of frames that they were alive before the ball went out; the reasoning being that the more often they returned the ball, the better the bot was at playing Pong.

Playing out a population in sequence

Playing out a population in sequence

As entertaining as it was to watch each match in realtime, we needed a faster approach before we considered evolving multiple generations. To achieve this we introduced a headless mode to the game that bypassed plotting graphics and just updated the in-memory game state. As no-one was watching these games we could also increase the frame rate. Together these changes reduced the time taken to evaluate a population down to fractions of a second.

The generation game

All that now remained between us and evolving King Pong was to implement the standard genetic algorithm loop. I covered much of this in my previous post so I’ll skim over it here. We used roulette wheel selection to choose bots to breed and performed crossover and mutation as specified by NEAT. Once this grunt work was done we could evolve the next generation from the initial population, repeating the process until we were satisfied with our bot’s Pong playing skills.

To help visualise the learning process we selected the fittest bot from each generation and played them sequentially:

Playing out the fittest from each generation

Playing out the fittest from each generation

Hitting the wall

Our bot was now evolving just enough to return the ball, but not a neuron more. Without another player the ball typically went out and it was game, set and match. In order to train the bot further we needed the other player to return the ball for another shot.

This is a perfect situation for coevolution. The idea is that we would evolve another bot that controls the second player alongside evolving the first. Their populations would be distinct, so no cross-breeding, resulting in their behaviour evolving much like an arms race: each time one player learns a new trick, so must the other player learn how to combat it.

As exciting as this would have been to try, we felt that this would complicate matters before we could confidently evolve a single player. Deferring that idea for now we simply replaced the other player with a solid wall. As every bored kid knows, a wall always returns a ball.

A perfect player against a wall

A perfect player against a wall

This small change resulted in our bot becoming more sentient than we had catered for. It soon learnt how to play the perfect game and our simulation never ended. To prevent this we introduced a timeout that would terminate the game after so many frames.

A beautiful mind

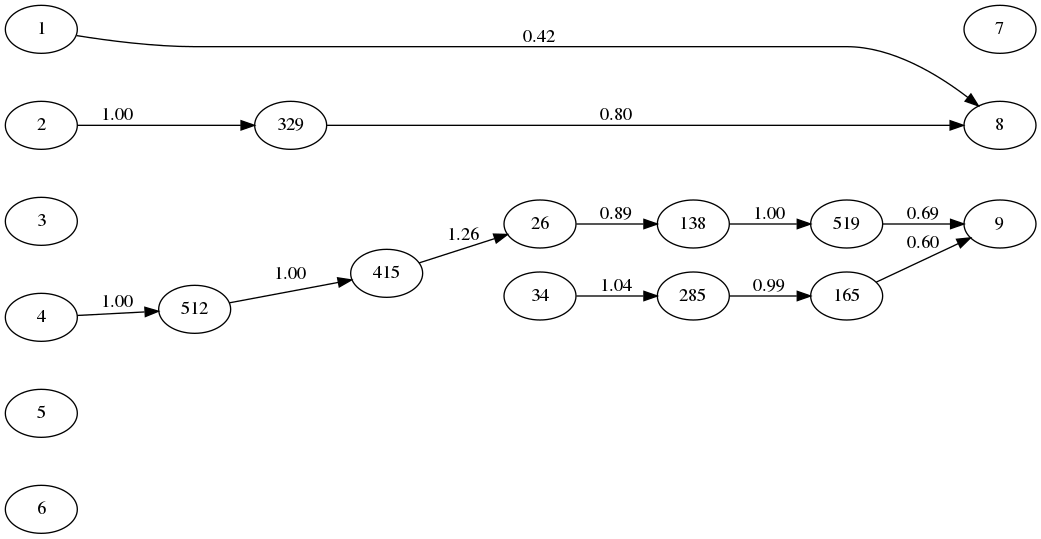

Now that we were getting some genuinely interesting behaviour we wondered what exactly we had evolved. To help visualise the bot we added support to output the neural network as Graphviz. Here is the genome playing the game above:

Matching the inputs and outputs to those described earlier, we can see that the bats’ positions are linked to moving up and the ball’s y-coordinate is linked to moving down. As the strongest signal wins, this network represents a seesaw between the ball position causing the bat to move in one direction, and the bat’s new position then causing it to move in the other direction. Note that there is some evolutionary deadwood here that has no net effect but was pivotal to obtaining this structure.

Insert more coins

At this point we thought it would be fun to tweak the game dynamics and see how it affected evolution. After reading about the history of Pong for some light relief, we learnt how the original game had a bug whereby the bat was unable reach the extremities of the screen. Allan, the creator of Pong, decided to rebrand this bug a feature so that even a perfect player had a chance of losing. After adding this to the game we noted that it actually slowed down training; presumably due to even perfect players losing and consequently their good genes being deselected.

It was becoming obvious that our simple ball collision mechanics made for rather predictable bots. In the original game of Pong, the contact point of the ball against the bat determines the ricochet angle. Implementing this would require the ball to have fractional velocity, and hence moving our game from lo-res to hi-res graphics. Unfortunately we ran out of time doing this as everything’s more complicated in an unquantised world.

One final aspect of neuroevolution that we didn’t touch on during this experiment was speciation. This protects innovation against ruthlessly pursuing survival of the fittest. We have since had a chance to revisit this and added preliminary support for species which resulted in much more sophisticated behaviour.

A bot evolved with speciation

A bot evolved with speciation

You can find our resultant neuroevolution library on GitHub, along with the Pong demo. Perhaps next time we’ll finish hi-res graphics, speciation, and coevolution. Until then, let us know if you have any success integrating it with other games and any feedback is always welcome.